My great-grandmother, Helene (Herline) Alter, claimed to be an orphan—but that wasn't exactly true!

Helene was born in 1886 in Hoboken, New Jersey, just across the Hudson River from New York City. Her roots were deeply planted in a proud German-American lineage. Her grandfather, Edward Herline Sr., was one of the “Forty-Eighters”—a group of intellectuals and reformers who fled the German states following the failed revolutions of 1848. A Bavarian artist by training, he established a thriving lithography business in the United States.

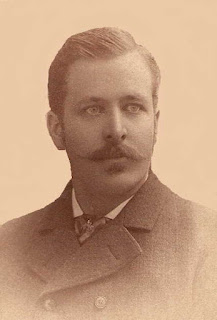

Helene’s father, Edward Otto Herline, initially followed in his father’s artistic footsteps but found his skills less in demand as printing technology advanced. He pivoted to sign painting, a trade that took him throughout the Mid-Atlantic and Great Lakes regions.

|

| Edward Otto Herline |

In subsequent years, there are scattered sighting of a similarly named man turning up in major cities like Cincinnati and Fort Wayne, but none can be definitively tied to Helene’s father. In 1918, Edward’s sister, Helen Lach, filed a legal claim against his property in New Jersey, summoning him via newspaper notice to appear in Hudson County Court. The implication was clear: Edward Otto Herline was either dead, missing, or in hiding.

But what of Helene and her mother?

By 1900, Helene’s mother—Elma Etta Ross—had remarried a man named Henry Truex and relocated west to Council Bluffs, Iowa, where Henry worked as a bartender at a local tavern. Helene, once a well-to-do city girl, was now a teenager in a rural town—and she wasn’t happy about it. At 16, she married a young man named John Kissel and moved to Denver, Colorado. Whether she ever saw her mother again remains unknown.

|

| Elma Etta (Ross) Herline Truex Becker |

Most remarkably, their mother never shared a word about her own parents. Helene claimed she was an orphan, and that was that. It was a story the family accepted without question for generations.

It wasn’t until I began my own genealogical sleuthing that the truth began to emerge. Elma’s marriage to Henry Truex seems to have lasted only a few years. By 1904, while Helene was living in Colorado, Elma had moved to Southern California with her aging parents, Hiram and Sabra Ross. Hiram, a Civil War veteran suffering from serious health issues, sought out the ocean air and nearby veterans’ services in Santa Monica.

Later that year, Hiram died, and Elma witnessed her mother’s application for a widow’s pension - signing her name as “Elma Becker” of Santa Monica. She was only 35 at the time and theoretically could have lived for decades more. But like Edward before her, after signing her name, she simply vanished from the records. We don’t know who Mr. Becker was, or whether Elma stayed in California. And we don’t know when—or where—she died.

|

| Helene Herline, not an orphan! |

We may never know the entire truth – but it’s a mystery I will continue trying to solve.

[[David Randall > Mary Edna Alter > Helene Herline > Edward and Elma (Ross) Herline]]