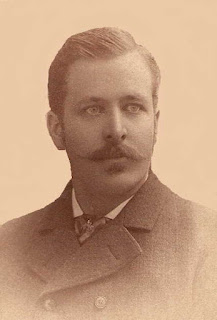

When it comes to couples, I’m fortunate to have photographs of my parents, my grandparents, all of my great-grandparents, and most of my second great-grandparents—some in multiple stages of life. But for this month’s “Couples” photo theme, I’ve chosen to feature a painting of my great-grandparents, Per and Elvera Johnson, the parents of my grandmother Leona Johnson, whom I wrote about in my previous post on “Language.”

This portrait has held a place of honor in my family for generations. It once hung at the top of the staircase in my grandmother’s home—a daily reminder of her parents’ legacy. After her passing, it moved to my mother’s bedroom, where it remained until her death last year. Today, it continues its quiet watch in my home, a silent connection to the generations who came before me.

My great-grandfather, Per August Johnson, was born on March 5, 1882, in Essex, Page County, Iowa, to Swedish immigrants James and Carolina (Peterson) Johnson. The third of seven children, he was raised on a farm in southwestern Iowa, where his family was part of the close-knit rural Swedish-American community.

Elvera Vendla Mathilda Bergren was born six years later, on March 23, 1888, in Grant Township, Montgomery County, Iowa—just a few miles from where Per grew up. She was the daughter of Gustaf and Christina (Anderson) Bergren, also Swedish immigrants. Like Per, she was the third of seven siblings and grew up on a rural Iowa farm, surrounded by the customs, language, and faith of her Swedish-American heritage.

Both Per and Elvera suffered a multitude of losses early in life. Per lost his 19-year-old sister Emelia in 1903 to what was recorded only as a “chronic illness.” Elvera’s eldest sister, Delia, died in childbirth at age 24 in 1907. She then lost both parents to consumption—now known as tuberculosis—her father in 1910, followed by her mother in 1911.

This portrait was painted from a photograph taken at their wedding on April 3, 1912, in Red Oak, Montgomery County, Iowa—just twelve days before the sinking of the Titanic. They settled in Fremont Township, Page County, where they began their family. Their first daughter, Leona, was born on January 16, 1913, followed by Eleanor on December 26, 1914.

The young family remained in Iowa through the 1910s, though sorrow continued to follow. Elvera’s brother Carl died of tuberculosis in 1913, her sister Edith died in childbirth in 1917, and Per’s mother Carolina passed away in 1919.

In 1919, Elvera herself contracted tuberculosis. At the time, there was no cure—her only hope lay in a change of climate. Like so many others afflicted with the “White Plague,” she moved west to Colorado, where the dry air, high altitude, and abundant sunshine were believed to offer the best chance of recovery. Per relocated the family to Boulder, and Elvera was admitted to the Boulder Sanitarium, a respected health facility modeled after Dr. John Harvey Kellogg’s sanitarium back East.

Located at the base of Mount Sanitas and operated by the Seventh-day Adventist Church, the Boulder Sanitarium specialized in holistic treatments for respiratory diseases. Patients followed strict diets, received hydrotherapy, and spent long hours outdoors in the mountain air. While Elvera fought for her life, Per was left to care for their two young daughters with the help of Elvera’s sister, the girls’ Aunt Esther. It was a difficult and uncertain time for the family—emotionally, physically, and financially.

Sadly, Elvera died on February 12, 1920. She was just 31 years old. Her death left Per a widower with two small daughters. Eighteen months later, Aunt Esther also passed away, leaving two young children of her own.

Later that year, Per remarried. His second wife was Bertha Johnson (no relation), the woman my grandmother would always call “Mommy.” Per and Bertha were married for 45 years, until his death on August 15, 1966, in Boulder. I was just nineteen months old at the time. Bertha lived another 18 years, passing away in April 1984.

Per and Elvera are long gone, but their legacy endures—not only in the century-old portrait that still hangs on the wall, but in the lives shaped by their experiences. Their love, losses, and quiet perseverance have left lasting imprints on the generations that followed—shaping us in ways we may never fully understand, but which continue to echo in our lives today.

No comments:

Post a Comment